This is part three of the essay “Putin’s Genocidal Quest for Symbolic Immortality”. Previous parts: (1) Introduction, (2) “Moscow is silent”.

Ukrainian human rights activist Maksym Butkevych volunteered to join the Armed Forces as a lieutenant immediately after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In June 2022, he was captured by Russian forces along with several soldiers from his platoon. As the Russians sought to break the spirit and will of Ukrainian prisoners of war, both physical and psychological torture became commonplace.

The first time Butkevych was severely beaten in captivity was over Ukrainian history. He and his fellow soldiers were forced to kneel before a Russian officer. The officer took out his smartphone and began reading aloud from Putin’s speech announcing the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 – focusing on the parts concerning Ukrainian history. The prisoners were ordered to repeat each line word for word. Every time someone stumbled, hesitated, or lost their place, the officer struck Butkevych hard with a wooden stick. By the end of the torture – and long after – Putin’s “history of Ukraine” was etched into Butkevych’s tormented body.1

Much of Putin’s speech was devoted to his multiple grievances about the West and its alleged political, military, and cultural threat to Russia. Western powers, he claimed, ignored Russia’s security concerns. The West is hypocritical and morally bankrupt. It forcefully imposes corrosive values on Russia – values that, according to Putin, run contrary to Russian traditions and weaken Russian society.

Yet the speech also featured Putin’s “historical” explorations of Ukraine – narratives that would later be used as part of the torture of Ukrainian prisoners of war. Putin denied Ukraine’s sovereignty by portraying it as historically and culturally inseparable from Russia. The idea of a sovereign Ukraine is framed as a Nazi endeavour and, therefore, as dangerous and illegitimate. Ukraine is depicted as a passive object manipulated by the West with the aim of weakening Russia.

Putin’s narratives on Ukraine build on his earlier pseudo-historical article, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians”, published about half a year before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and widely seen as the “theoretical” preparation for it.2

The article proceeded from the premise that Ukrainians are, in fact, Little Russians (malorosy), who – together with Great Russians (velikorossy) and White Russians (belorusy) – comprise the single, large Russian nation. The Ukrainian national project, which rejects the “Little Russians” construct, is thus portrayed as illegitimate, artificial, and the product of foreign interference. The article concludes that Russia has a fraternal duty to preserve “the unity of Russians and Ukrainians”, casting Ukrainian independence as both a historical error and a geopolitical threat.

Putin’s “history” of Ukraine is less his own creation than an echo of older, inherited myths. In 1975, the year Putin joined the KGB, Yulian Semyonov wrote another novel about Stierlitz, A Third Card, which placed significant focus on the Ukrainian national-liberation movement – a movement the novel sought to discredit.3

The timing of the publication was anything but accidental. In 1975, nearly all European countries – along with the Soviet Union, the United States, and Canada – signed the Helsinki Final Act, a non-binding political agreement aimed at improving relations between East and West during the Cold War.

The Final Act was the outcome of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, and covered security, economic cooperation, and human rights. In particular, the document argued that all peoples have the enduring right to freely determine their internal and external political status, and are free to pursue their political, economic, social, and cultural development as they see fit. Moreover, the signatories agreed to “respect the equal rights of peoples and their right to self-determination”.4

In several Soviet republics, in particular in Ukraine, Baltic republics, Georgia, and Armenia, the Final Act energised national-liberation and human rights movements that increasingly demanded greater national cultural rights, autonomy, and even independence. The formation, in 1976, of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, was a notable example of the developments. The Group directly cited the Final Act in its attempt to press the Soviet authorities for compliance with human rights and national self-determination. Hardly surprising, the Soviet regime viewed such movements as a threat and unleashed repressions against them.

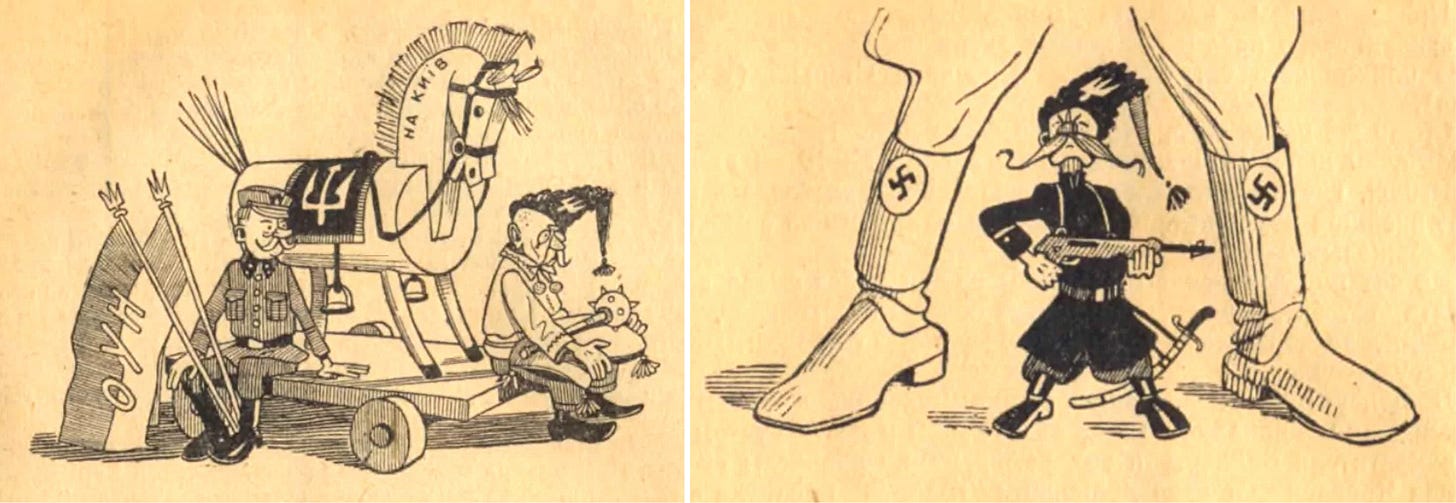

Repressions against members of national-liberation movements – Ukrainian in particular – ranged from “soft” measures such as surveillance, harassment, censorship, and forced emigration, to more severe tactics, including physical violence, long-term imprisonment in labour camps, and punitive psychiatric hospitalisation. There was also a more subtle form of repression: cultural warfare. The novel A Third Card, written by KGB collaborator Yulian Semyonov and aiming to demonise the Ukrainian national-liberation movement through fiction, exemplified this approach.

Like all other Semyonov’s works centred on Stierlitz, A Third Card blends elements of historical reconstruction, spy thriller, and alternative history. The novel transports the reader to 1941 – a key turning point in Soviet history – when Nazi Germany launched its invasion of the USSR. Moscow’s agent, Stierlitz, is tasked with destabilising the enemy from within by exploiting tensions between the SS and the Wehrmacht, and using Ukrainian nationalists collaborating with the Nazis, namely the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) led by Stepan Bandera, to further inflame the divisions within the fascist establishment.

The novel associates the vision of a sovereign Ukraine independent of the Soviet Union with Bandera and his followers (Banderites), portraying the idea of Ukraine’s independence as a criminal enterprise instrumentalised by the Third Reich. In doing so, it strips Ukrainians of both dignity and historical agency. The Abwehr “promises” the OUN an independent Ukrainian state, but among themselves, German officers admit that Ukrainian nationalism is nothing more than a “paper handkerchief” – to be used and discarded once it has served its purpose in the war against the USSR.

In this narrative, the idea of the Ukrainian national project becomes an expendable and ultimately redundant “third card” in the geopolitical games of greater powers. Without the Soviet Union, Ukraine is a territory without a future – effectively a colonial void, to be shaped and occupied by stronger forces. Ukrainians themselves are portrayed as incapable of building or sustaining an independent state.

But the novel also had a twist. A Third Card was Semyonov’s eighth novel featuring Stierlitz, but it was the first to reveal – hardly by accident – that the Soviet spy Vsevolod Vladimirov, who operated under the alias Stierlitz, had both Russian and Ukrainian roots. His father was Russian, while his mother was Ukrainian – the daughter of a “Ukrainian revolutionary” exiled to Transbaikalia by the Russian tsarist regime for his political activities. This detail implied that Vladimirov’s mother had an ideologically correct biography: in Soviet terminology, a “Ukrainian revolutionary” was understood to be part of the progressive Ukrainian forces whose struggle for socialism was seen as aligned with, and part of, the broader revolutionary cause shared with Russians.

Vladimirov’s family background did not, however, make him “half-Russian, half-Ukrainian”. Semyonov’s “revelation” simply meant that Vladimirov’s biographical Ukrainian-ness was just a stream flowing into the river of Russian-ness. Vladimirov/Stierlitz embodied the “historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians” as understood through the lens of the Russian colonial paradigm.

Thus, Semyonov’s novel A Third Card presented two very different types of Ukrainians. One type comprised criminal Banderites, manipulated by anti-Russian forces into imagining the creation of an independent Ukrainian state as a means to undermine the Soviet Union. The other type consisted of Ukrainians whose Ukrainian-ness was subordinated to Russian ethnocultural identity and integrated into the “Great Russian” nation. The first type was dehumanised through association with fascism; the second was humanised through its relationship, albeit unequal, to Russian ethnicity. It was Ukrainians of this second type – fully integrated into Russian culture, with their Ukrainian-ness reduced to family names or a slight accent – whom Putin saw around him in the KGB, and who, indeed, differed little from their ethnically Russian colleagues.

It is easy to imagine that A Third Card had a direct impact on how Putin, then a 25-year-old KGB recruit, came to perceive the Ukrainian national project. Yulian Semyonov’s novels were immensely popular in the Soviet Union – Stierlitz was a Soviet “James Bond” – and Putin himself admitted that he was fond of Soviet spy thrillers in his youth.5

Even if this assumption may seem far-fetched, it is worth remembering that Semyonov was a KGB collaborator, and the political themes in A Third Card were not merely random fiction, but reflected the KGB’s prevailing views on the “Ukrainian question” at the very time Putin began his career in the agency. There is little doubt that he internalised the KGB’s stance on the Ukrainian national project through both his service and the literary products of Soviet cultural propaganda.

Moreover, Semyonov’s distinction between two social types of Ukrainians was neither his own invention nor that of the KGB. By the time he was writing, these stereotypes had long been established. Mykola Riabchuk traces their origins to the 18th century: on one hand, the “Little Russians” – “educated, loyal and basically integrated into the imperial culture”; on the other, the khokhly – “illiterate local peasants [...] with a crude but picturesque aboriginal culture and a strange dialect”.6

The rise of nationalisms across Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe at the end of the 19th century, and the collapse of European empires in the early 20th century, gave momentum to the Ukrainian national-liberation movement, which was ideologically diverse, ranging from the far left, through the centre, to the far right. However, in the Russian colonial typology of Ukrainians, the figure of the “illiterate local peasant” – who, under the malign sway of anti-Soviet foreign powers, dared to dream of an independent Ukrainian state – was crudely recast as the criminal, fascist Banderite. The stereotypical “good Little Russians”, however, remained unchanged: they were those who accepted the primacy of “Great Russian” culture and were essentially regarded as part of “the single, large Russian nation”.

Ironically, Ukraine became independent in 1991 not through the nation-building efforts of the “Banderites”, but as a result of Moscow’s “paralysis of power” that led to the fall of the Soviet Union. However, Ukraine’s initial post-1991 sovereignty posed little concern for the Kremlin. As the country struggled through the collapse of the planned economy, hyperinflation, flawed privatisation, energy dependence, and population decline – all exacerbated by pervasive corruption – it remained firmly within Russia’s sphere of influence. For Moscow, this seemed to confirm a long-standing belief that khokhly were incapable of sustaining a truly sovereign Ukrainian state. And as long as Moscow-friendly “Little Russians” held power in Kyiv, the Kremlin was content to tolerate Ukraine’s formal independence.

Yet as Ukrainian civil society matured, a series of intense popular protests increasingly challenged the rule of “Little Russians” in Ukraine, culminating in the 2014 national-liberation revolution that toppled the regime of pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych. For Putin, this was a sinister echo from the past – a replay of the traumatic events he had witnessed in Dresden: a popular movement asserting democratic sovereignty by rejecting the rule of Russia’s puppets in a country Moscow believed to be a satellite state. “Ukraine is Europe!” – the slogan popular during the 2014 revolution – was the Ukrainian version of “Wir sind das Volk!”. The revolutionary movement spoke on behalf of the people of Ukraine and made a clear geopolitical choice: away from Moscow, and towards a united Europe.

However, the 2014 revolution in Ukraine was, for Putin, even more threatening than a replay of the Dresden events. Unlike in the GDR in 1989-1990, it was not merely ordinary citizens who challenged Russia’s political and cultural dominance in the region – it was nationally conscious Ukrainians, representatives of that dangerous type in Russia’s imagination, who were immediately identified by the Kremlin as fascists manipulated by the West to harm Russia.

This configuration added a new dimension to the blow to Putin’s sense of symbolic immortality, which was centred on survival through the state: Ukraine’s national self-determination. He came to see the very existence of the Ukrainian nation – which clove asunder the “Great Russian” state and, with it, the psychological armour shielding him from existential dread – as yet another rupture that could be repaired.

Unlike in Dresden in 1989, Putin made sure that Moscow would remain silent no longer. The war against Ukraine began.

Continue reading: Part Four, “A fascist coup!”

Butkevych survived the Russian captivity, and was released in October 2024 in a prisoner swap between Ukraine and Russia. See also “Life After Captivity and Justice for Ukraine. Maksym Butkevych and Misha Glenny in Conversation”, Institute for Human Sciences, 19 March (2025), https://www.iwm.at/event/life-after-captivity-and-justice-for-ukraine.

Vladimir Putin, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians”, President of Russia, 12 July (2021), http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181.

Yulian Semyonov, “Tretya karta”, Ogonyok, Nos. 37-52 (1975).

“Helsinki Final Act”, OSCE, 1 August (1975), p. 5, https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/5/c/39501.pdf.

Ot pervogo litsa. Razgovory s Vladimirom Putinym (Moscow: Vagrius, 2000), p. 24.

Mykola Riabchuk, “Ukrainians as Russia’s Negative ‘Other’: History Comes Full Circle”, Communist and Post-Communist Studies, Vol. 49, No. 1 (2016), pp. 75-85 (77). Today, “khokhol” (singular) and “khokhly” (plural) are derogatory ethnic slurs used against Ukrainians.